Is ‘Smart’ Really a Thing?

Is “Smart” really a thing?

I have a distinct memory from my time in elementary school of realizing that being smart is a very relative thing. The fact is, even elementary school students can understand that there’s a grey area when it comes to “intellectual prowess”: it is weird, in that way, that we try to decide and define who is smart and who isn’t. Sometimes, there are outliers of course - no one would ever really try to fight me if I said that Einstein was a genius. And yet, to me “smart” remains a very loaded word.

The main aspect of “smartness” I was thinking about in lower school was smartness in a multitude of categories: even if I may be book smart, for example, I have a very difficult time understanding people, and when it comes to social interactions I’m relatively hopeless. Smartness, from my perspective, ought to be considered more like (and forgive my references here) a Dungeons and Dragons character sheet rather than as some individual thing that measures solely how much someone has memorized flash card.

As a society, we’ve definitely been moving in the correct direction – standardized testing becoming optional for many schools is one of the first steps to recognizing the multitude of “smart” categories of students, and it will likely bring about a great degree of change for the better in multiple institutions. There obviously remains a long path to this recognition, however, and to that extent I’ve come up with a few paths I think might be able to be followed. The primary goal of these paths, or initiatives, would be to actively support the “smartness” of students not only in their intelligence, but in their five other categories as well (although I will mainly want to focus on Constitution, Wisdom, and Charisma).

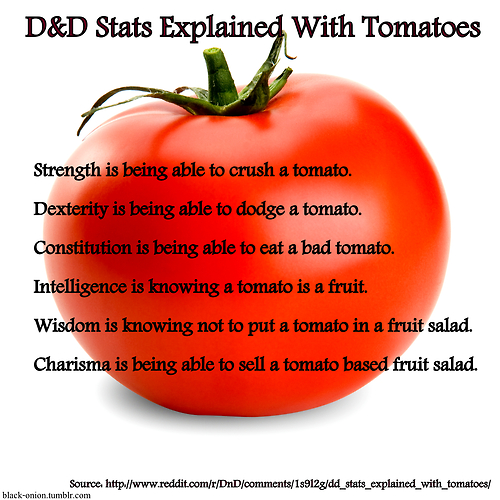

For those unitiated in Dungeons and Dragons, I’ve provided a short, handy example of each of the six stats explained using tomatoes.

Based off of the DnD chart:

- (Constitution): How often has there been a friend that is just inherently in tune with their own body? This applies particularly to athletes and to dancers; the reason why I’d say that this falls under my terminology for “smart” is that this is a skill, based in understanding, that must be incessently worked at. Over time, you need enough experience with moving, working out, or playing games to understand yourself. The best way that we might begin incorporating a greater degree of respect for this “smartness” would likely be similar to the gym classes we have now; however, it relies on the coaches or teachers leading these activities encouraging learning about physical improvement, and applauding personal growth (not just natural skill)

- (Wisdom): This is street smarts, and although it can’t really be taught, it is always good to introduce new material to kids in class. I think running small sessions of activities that have unexpected or unrecognizable projects would aid in improving “wisdom smartness”.

- (Charisma): This one is quite important, and quite often overlooked. Charisma is a trait that is often built up from a very young age, and I know that I for one struggle with it. This smartness was my primary inspiration for thinking this in elementary school; knowing social interactions, when to speak, what is funny to say, when to say it, is difficult. As adults we’ve honed in on proper timing in converstaions, or proper topics to discuss, but as children most of the time this is only learned through peer-to-peer interaction. I’d say that in this case, the problem is less about teaching Charisma “smartness” and more about acknowledging it; potentially in school, especially lower levels of schooling, taking time to acknowledge feats of charisma, or running small programs where students share what they admire about how other people interact with them. The main point here is cognizance of the importance of social awareness.

There’s something to be said for teachers and mentors being involved outside of the classroom. I think at the end of the day, what I really wanted to get across with this post is the fact that students should acknowledge a variety of talents that they have, not just the ones that they demonstrate via memorization or in class.